Warning: Spoilers – lots & lots of Spoilers from the Trilogy. Don’t read if you don’t want to know

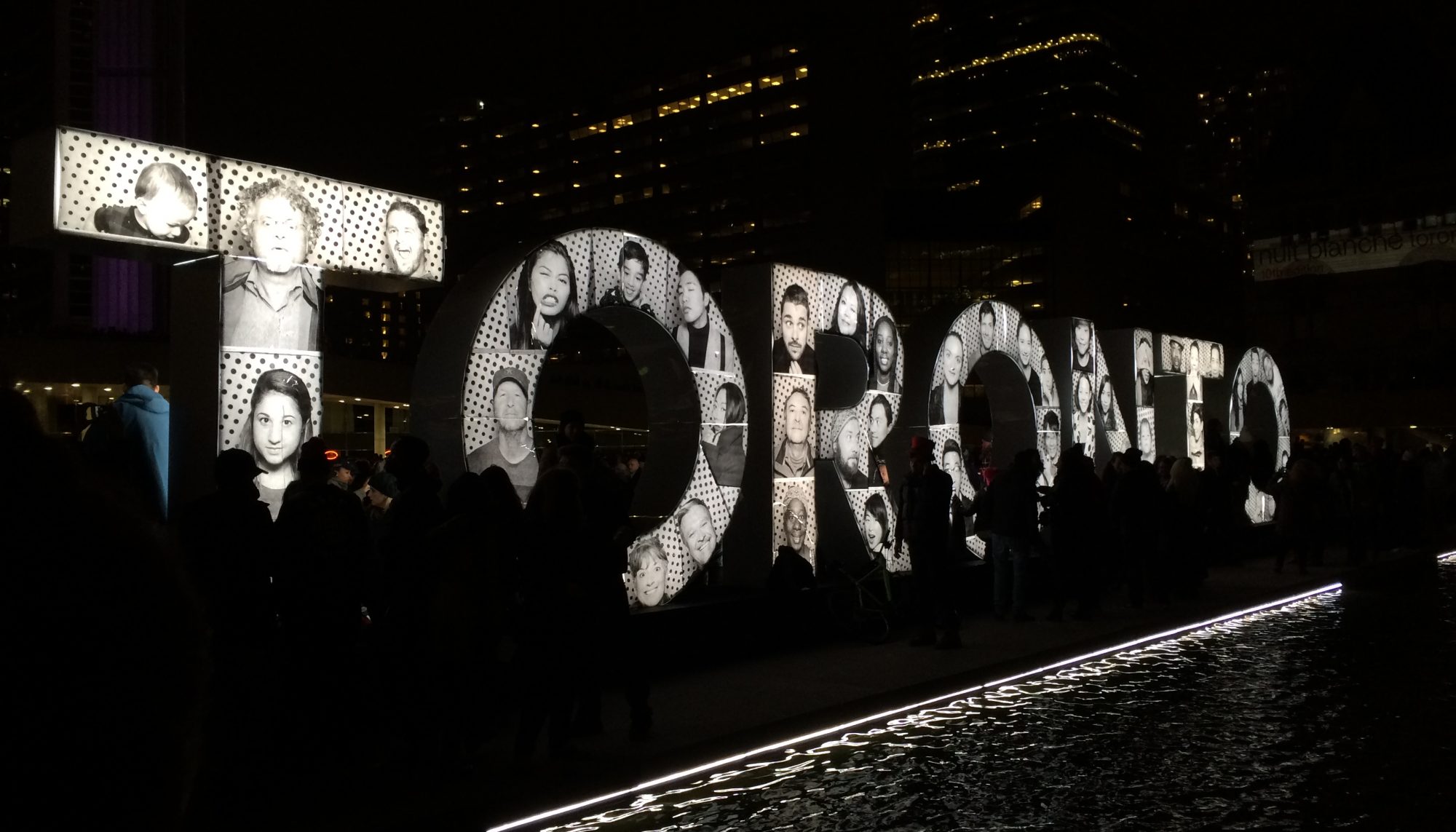

Have you read The Hunger Games? the full series? been on the Facebook Capitol PN or District pages lately? Dipped into the Twitter feed #LookYourBest?

If you have, you may have noticed something really odd. If you’ve read the first book (now in theaters near you & soon to be released in IMAX!), then you know that Katniss Everdeen volunteers to be a tribute to save her sister, Prim, from certain death.

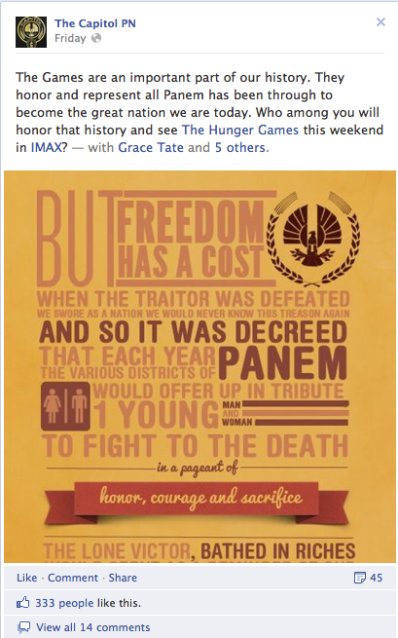

In the first novel, we see the poverty of District 12, learn about the uprising of the 12 Districts against the Capitol, the ensuing annihilation of District 13, the brutal subjugation of the remaining 12 Districts and the founding of the Hunger Games as a reminder of the destruction that rebellion & civil war lead to.

In The Hunger Games, Suzanne Collins’ story exemplifies what I have come to see as the moral core of children’s literature, which I have taught roughly twice a year for 10 years now. The power & the truth of children’s lit lies in the valuing of a child’s point of view, which in the ‘real’ world, we adults view as immature, naive, ignorant, etc etc, in contrast to the more mature, nuanced & complex understanding adults have as a result of experience, knowledge, and wisdom, as the result of more time spent on earth.

The moral core of good children’s lit is the absolute assertion of the value of the individual relationship against arguments of sacrificing one or many for the greater good. Children refuse to treat others as objects, affirming instead subject to subject relationships. You see this in Huckleberry Finn, where Huck cannot betray the immediacy of his friendship with Jim, even though he believes helping a runaway slave is wrong & will land him in hell. And in Twain’s extended critique of Tom Sawyer’s cruel victimization of Jim in the final section, when Tom directs a prolonged, unnecessary prison escape, despite knowing that Jim is now free.

It’s there in The Golden Compass where Lyra always commits to helping those who are being victimized, and she consistently positions herself against the adults in power who kill the weak for the greater good: the children at Bolvangar, Roger… Philip Pullman makes this contrast explicit in Mrs. Coulter’s and Lord Asriel’s complete lack of empathy for those they torture & kill respectively.

This moral core is fundamental to Rowling’s Harry Potter series, as Harry, Hermione, Ron & Dumbledore’s Army consistently choose to fight Voldemort’s totalitarian regime. And most importantly, what Rowling makes absolutely clear is that her characters assert their love for one another, and that those bonds exist as an aspect of identity and community that are worth self-sacrifice, as Harry shows us in the final book, but never the sacrifice of others as symbolic, token or necessary substitutes. In the film version of the Half-Blood Prince, Dumbledore says to Harry, “Just like your mother, you’re unfailingly kind. A trait people never fail to undervalue, I’m afraid.” Throughout the series and across generations, Rowling repeatedly sets kindness against cruelty, and in the final battle, we see the impact of those forces on different character arcs (Neville, Luna).

So, if you’ve only read The Hunger Games, the first novel seems to hew closely to this model. The Hunger Games are an annual sacrifice of two youths for the greater good, Katniss’ volunteering for her sister is a self-sacrifice that saves her sister from experiencing a horrible death played out as spectacle for the entertainment of the Capitol and which the Districts are obligated to witness.

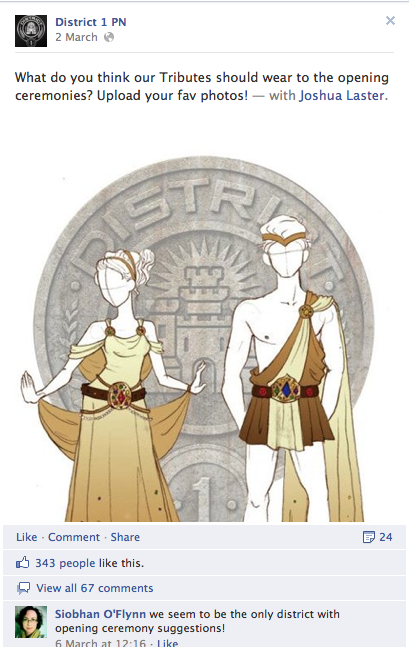

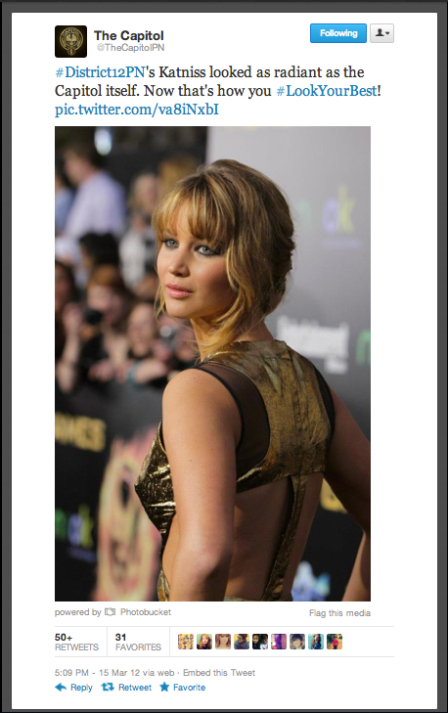

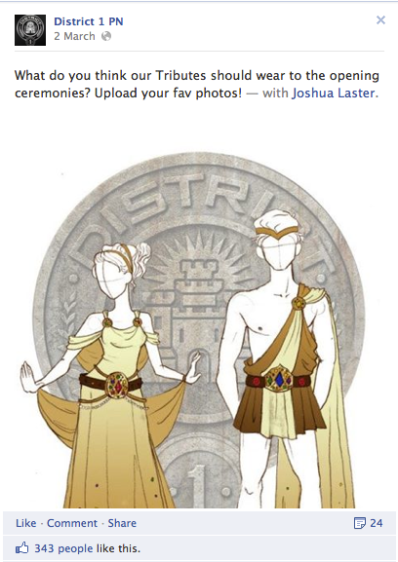

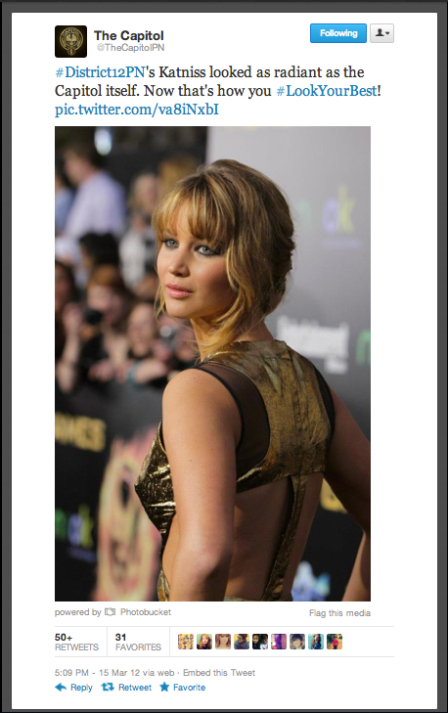

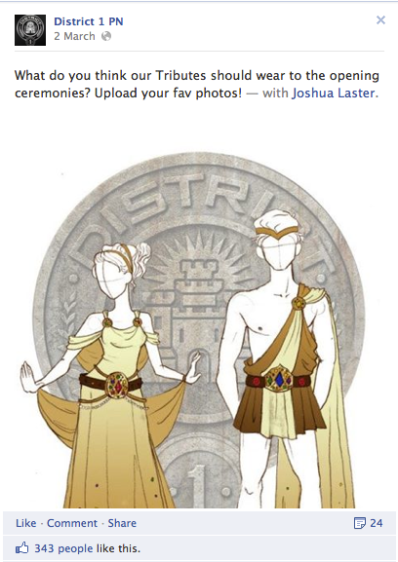

And here’s where the novel starts to become tricky – Katniss’ preparation for the Games by her team of stylists is both glamourous and an enactment of the power of the state on the body of the subjugated. As Collins repeatedly tells us, Tributes are often sent into the Opening Ceremonies in stylized nakedness and as Katniss is waxed and groomed, she is grateful that her team stops short of radical body modification. The novel tenuously balances Katniss’ resistant pov on her transformation into the most beautiful girl at the Games and the seductiveness of luxury that is the central focus of the Twitter hashtag, #LookYourBest and the messaging of the Facebook Capitol and District pages.

Here’s where the disjunction between the novel(s), the marketing, and the reception start to get really strange. If you’ve read the Trilogy, then you know SPOILER! that Katniss takes on the role of figurehead leader of the revolution of the Districts against the Capitol, that she is manipulated by the leader of District 13 (not dead after all), by Abernathy, by Cinna, that Prim is killed in an unconscionable attack on the children of the Capitol, and that Karniss becomes a morphling (morphine) addict who is repeatedly being medicalized against her will, spending what seem to be numerous stretches in opiate induced unconsciousness.

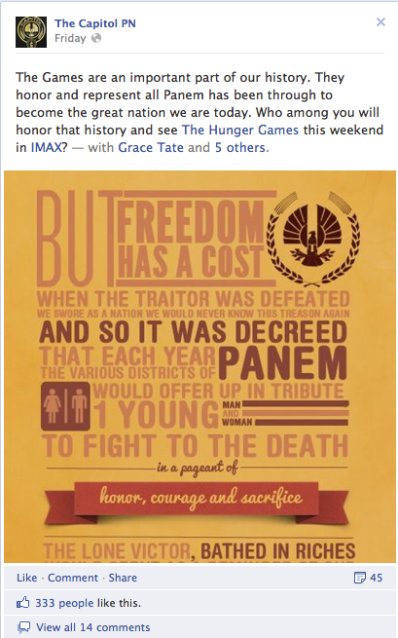

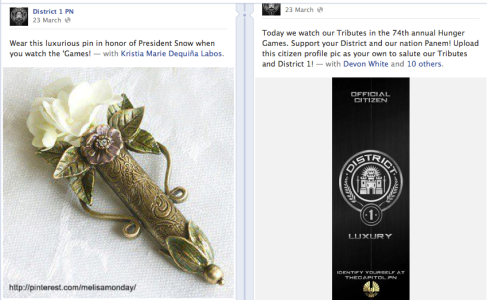

That Lionsgate has made identification with the Capitol and the vacuous, privileged, style & spectacle obsessed residents of the Capitol the focal point for fans of the series is an unbelievable misstep in terms of what the series depicts as the evil at the heart of what America has become. So if you’ve read the series, images such as these are weighted with the problematic identifications we are asked to make – to President Snow, to the Capitol inhabitants who enjoy watching youth being maimed & destroyed.

In the screen shot below from The Capitol Facebook Page, the invitation to wear a white rose to ‘honor President Snow’ is distinctly problematic, given the sadistic inventiveness of the torture enacted in the Games & the violence that follows the uprisings.

Collins also makes clear that Katniss’ final choice [SPOILERS!] of killing President Coin (no accidental name here) is an act to protect the future, where the shooting of President Snow would have avenged the past. This is explicit in the contrast between Katniss and her best friend/erstwhile boyfriend, Gale, who chooses a different path, designing death traps that intentionally sacrifice the innocent for the greater good. The fact that she and he can never know for sure if his strategem killed Prim and the hundreds of Capitol children she had rushed to help is a deciding factor in Katniss (finally) choosing Peeta (which we don’t see in the novel).

What is most difficult about the series & where it is distinctly NOT Harry Potter, is that Katniss’ story, told in first-person, is the story of a teenager suffering acutely from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder without relief. The first-person voice is strategic as it means that Katniss is initially ignorant of how she is being manipulated by both sides, President Snow & District 13 leader, Coin. What it means though is that we experience Katniss’ world & story from within an extremely traumatized psyche. Unlike Rowling’s series, Katniss has no community, no network of friends, and bluntly, there is no joy in the series, which the Harry Potter series has in abundance with the affirmation of friendships and love, and the delight and wonder of the magical world. In contrast, Katniss is repeatedly betrayed by those she trusts, trauma is inflicted on her repeatedly, in the first games, then the 75th Games, where all surviving Victors compete against each other. Finnick & Annie’s wedding in The Mockingjay is a brief moment of relief and yet, Katniss is superficially engaged and Collins then kills Finnick.

Why then is this a series that speaks to its audience now?? It’s not just the parallels between the novel’s dystopic vision of a future America and the polarization and activism that has sprung up around the Occupy movement and its language of the 1% and 99%. And to be frank, this critique seems to be completely missing from the engagement Lionsgate invites and the role-playing fans engage in dressing up as Effie or playing tributes on the various online games.

What no one to my knowledge has flagged are the parallels between Katniss’ acute experience of PTSD (one could add Peeta, Haymitch, & all the other victors here, with the nightmares, the constant fear of attack), the descriptions of her physically traumatized body with the extensive burn scarring and the parallels to the phenomenon of PTSD in American military personnel returning from Iraq & Afghanistan. Here too, Peeta’s loss of a leg resonates, even though he has been fitted with a high-tech prosthesis. As a Canadian, not living in a country militarized to the degree that the US is now, I have to ask if the dystopic vision of The Hunger Games series is a mediation of what seems from across the border to be an awareness of the challenge of reintegrating the severely traumatized veterans of the War on Terror.

Nicholas Kristoff has reported that for every American soldier’s death in Afghanistan and Iraq, 25 military veterans commit suicide (TWENTY-FIVE), one every 80 minutes. That is an astonishing, devastating phenomenon. In this context, I cannot but read The Hunger Games series as a reflection on and mediation of the scarred bodies and psyches of those who return who, like Katniss or Haymitch, are barely able to connect back to an everyday life of normalicy. Collins gives us a snapshot of the future, Katniss & Peeta in the future with children, yet Katniss is clearly still scarred, not surprisingly.

So when my 13 year old daughter tells me that she loves The Hunger Games and that on reading The Mockingjay for the second time that she started crying on the first page & didn’t stop until the end, I’m not surprised. The degree of violence, victimization and brutalization surpasses that of Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker, Kimberley Pierce’s Stop Loss, or even Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (yup, I’m going that far). The sadism enacted in the series matches or surpasses the details of Charles Taylor’s regime that have hit the news this week.

There may be some parallels between Collins’ series and Rowling’s, but they are absolutely not the same in tone or experience. It might be time to start asking why this series resonates now, what fans are responding to, and what is actually being critiqued in the novels. Having read the series, how Lionsgate is going to adapt the following two novels for a PG-13 audience is beyond me as the current marketing of the film through its ARG extensions firmly positions the audience in the role of those who oppress and torture. Good luck, Lionsgate.

Nicholas Kristoff’s article here: